Andy Weir's latest, Project Hail Mary, is a good book that you'll almost certainly enjoy if you enjoyed Weir's freshman novel The Martian. It's another tale of solving problems with science, as a lone human named Ryland Grace and a lone alien named Rocky must save our stellar neighborhood from a star-eating parasite called "Astrophage." PHM is a buddy movie in space in a way that The Martian didn't get to be, and the interaction between Grace and Rocky is the biggest reason to read the book. The pair makes a hell of a problem-solving team, jazz hands and fist bumps and all.

Project Hail Mary

I get it—that's how storytelling works. I don't want to sound like a bitter basement-dwelling critic throwing shade at a bestselling science fiction author. But PHM is like The Martian in that it's about solving problems realistically. From my nerd basement throne, it feels like the softer sciences of linguistics and anthropology (or perhaps xenolinguistics and xenoanthropology) don't get the same stage time as their more STEM-y counterparts like physics and relativity.

Indeed, Grace quickly builds a workable level of rapport with his alien counterpart:

The acquisition of a wholly alien language is treated like a math problem—a series of steps that, if completed in the right order, guarantees comprehension. Our two intrepid interstellar explorers find each other in the void and start cooperating. They link their ships and figure out the pure mechanics of communication. Both use sound, though Rocky communicates with chords and whistles. Grace has a laptop with a copy of Excel and some Fourier transform software, while Rocky has an eidetic memory, so the physical layer of communication is easily handled. They quickly work out equivalent words for things around them, like "wall" and "star" and "Astrophage." They also knock out "yes" and "no" through some quick pantomime, followed by "good" (or at least "I appear to approve of this") and "bad" (or at least "I appear to disapprove of this").I pull the jumpsuit on. I've decided today is the day. After a week of honing our language skills, Rocky and I are ready to start having real conversations. I can even understand him without having to look at the translation about a third of the time now.

After some more language learning, we come to this particular passage—the passage that pushed me over the edge into writing this piece:

Proper nouns are a headache. If you're learning German from a guy named Hans, you just call him Hans. But I literally can't make the noises Rocky makes and vice-versa. So when one of us tells the other about a name, the other one has to pick or invent a word to represent that name in their own language. Rocky's actual name is a sequence of notes—he told it to me once but it has no meaning in his language, so I stuck with "Rocky."

But my name is actually an English word. So Rocky just calls me the Eridian word for "grace."

How, exactly, does one build the necessary cognitive scaffolding—in a period of time measured in weeks—to explain "grace" to an alien that may or may not have the emotional wiring to even conceptualize the word? And if the alien does have an equivalent word, how do you know with any amount of certainty that the word means the same thing? "Grace," after all, is a squishy concept involving morality and value judgments. A huge array of other concepts have to be settled with equivalencies before you can even begin to understand whether or not, when the alien says "grace," it means the same thing to each speaker.

All of which made me wonder whether the language learning portrayed in PHM was, well, realistic.

Head games with foreigners

Sci-fi does offer us many other visions of alien communication. I'm no linguist, but I do read a lot—and one of my favorite authors is the inimitable C.J. Cherryh, arguably one of the last living grand masters of science fiction. Cherryh's specialty genre might best be described as "anthropological SF," due to her academic grounding in archaeology and mythology. She has a knack for writing alien characters that finely manage the balance between being interesting and also truly, believably alien—not just in form, but in motivation and emotion. And Cherryh's work, to pick on her as an example, posits a hell of a lot more difficulty in communicating with aliens.

Though her body of work stretches back to the 1970s, Cherryh's knack for getting the alien/human interface right is shown off to great effect in her Foreigner series of novels, which features a lone human translator living among an emotionally incompatible race of aliens called atevi. Atevi are superficially much like humans—a bit taller, different skin color, but they're bilaterally symmetric humanoids with two arms and two legs and a head. They look more or less like us, and that's how the problems start.

Humans show up at the atevi home world accidentally, since it's the only habitable refuge a failing and lost human colony ship can reach with the ship's remaining supplies. Although the atevi are barely past the steam age, the two peoples have a peaceful and productive first contact. Things go really well for a few years—humans start to integrate into atevi society and freely share their technology.

Then, suddenly, war breaks out. Neither side really understands why. Shortly before the small human population is annihilated, though, a ceasefire is reached. The two sides take a step back to try to figure out why they started fighting, and working the issues out for the reader takes most of the first book in the series.

The top-level reason, as it turns out, is that even though both races thought they were communicating with each other, the semantic equivalencies they built were completely misaligned—and one race's idea of "friendliness" was another race's idea of "pure lunatic insanity." Cherryh dwells on the idea that language is at least partially a product of phylogeny. When you and an alien use a word, your individual understanding of that word hinges on a whole host of factors that you share with others of your species, but you and an alien may not have such context in common at all. Both races, human and atevi, were acting logically from their own point of view—and both races, from the other's perspective, were responding to logical acts with apparent psychotic craziness.

Think of how much of human language and understanding is built on inherent, foundational concepts—our biology and base perceptions are part of the fundamental structures of language. If I as a human am attempting to somehow talk with another human with whom I have no language in common, we can still build certain assumptions into our attempts at communication. Even if I'm speaking to a member of an isolated or uncontacted culture, we both will have similar underlying biological drives. If we can figure out each other's word for "love," for example, I don't have to explain what love is. We both just know. Dig far enough down and we'll always find some semantic bedrock on which to build a conversation.

Actual understanding isn't just a process of establishing equivalencies—it's a much more complex web of ferreting out the underlying concepts behind the words and checking how (or even if!) those concepts map to their counterpart concepts on the other side. Sometimes—often, in fact, with Cherryh's atevi—no useful correlation is possible. Atevi biology and evolution has produced fundamentally different emotional drives than human evolution produced. Atevi don't feel love or friendship, instead they have their own emotional response based around hierarchical grouping. It's just as powerful and fulfilling as love and friendship—and it serves the same useful function of creating and enforcing cooperation and societal cohesion—but actually explaining what it feels like in human terms is impossible. (There's so much more to Cherryh's atevi, by the way. If you're in the mood for a cracking good read, I suggest you grab the first book in the series and dig in!)

So which take on extraterrestrial language acquisition hews closest to reality?

I say potato, you say 🎶🎶🎶

Again, I don't know. I'm just a guy who writes about farts on the Internet. I needed to call in the big guns—actual smart people with actual degrees in the talky sciences.

Dr. Betty Birner is a professor of linguistics and cognitive science at Northern Illinois University. Dr. Birner's specialty is the field of pragmatics—which she summarized for me as the difference between the words someone says and the intention behind those words. Pragmatics includes the study of how we as speakers of a language use inferences about intent—inferences sometimes built on inherent assumptions about context, which themselves can stem from biological underpinnings—to overcome language's ambiguities.

The question I put to her was this: going by our current understanding of how and why human languages operate, do we think it would be practical—or even possible—for two divergently evolved sentient beings from different worlds to learn each other's languages well enough in a short amount of time (perhaps as little as a week) to usefully converse about abstract concepts and to be reasonably assured that both beings actually understand those abstracts?

I asked Dr. Birner if she could help me understand the commonalities that show up between human languages and what separates language (which requires structure) from communication (which is something most animals manage to do without language). It's a hard subject to nail down, but Dr. Birner cited the work of Dr. Charles F. Hockett and pointed out that there are several broadly accepted criteria for what makes a language a language. One of those criteria is the concept of syntax.

"Human languages all have syntax," she explained. "You have distinct pieces that you can put together in different orders to get different effects. Even sign languages have this. No animal communicative system has it."

"How can I possibly ask an alien, 'What's your word for friendship?'"

Beyond syntax, another feature of language is the concept of displacement. "I can talk about things," she said. "Distance, and time, and place. Your dog can't do that. Your dog can scratch at the door to communicate that she wants to go outside, but she's not going to be able to say she wanted to go outside yesterday."

Dr. Birner's own specialty field of pragmatics has its own take on what makes language, language: a thing called the cooperative principle. "The basic notion is that when we communicate we are cooperative in some very fundamental ways," she said. "We say the right amount. We say things that are relevant. We say things we at least believe to be true. So, we have all these assumptions also about the other person being cooperative, and if we didn't believe they were trying to be cooperative in all of these ways, communication just couldn't work."

I pointed out that as a lay person, the most interesting part of this to me is how we selectively break the cooperative principle all the time—for humor, or for sarcasm, or whatever. Breaking the cooperative principle imparts its own messages, and Dr. Birner agreed.

"Absolutely—that's part of the cool thing about the cooperative principle," she laughed. "We violate it! So there's a maxim of the cooperative principle that says, 'Say only what you believe to be true.' Well, we violate that all the time in metaphor. 'You are the light of my life.' Well, no, you're not a bunch of photons. Clearly this is false. But you infer away about what I actually meant. So, yeah, how do we know that anything that's true of human language is true of an alien language?"

You gotta Noam when to hold 'em

Dr. Birner also (perhaps inevitably) brought up Noam Chomsky, the world-famous linguist. He's responsible for, among other things, the idea of some form of universal grammar existing in humans. We can speculate about whether or not Chomsky's theories are true for humans, but can we safely extend those theories to cover hypothetical sentient alien life that evolved in a completely different environment?

"He [Chomsky] has a notion," she said, "that there is an innate biological instinct for language in human beings—that language is instinctive to me in the same way that spinning a web is instinctive to a spider. He almost single-handedly killed behaviorism back in the fifties, because in behaviorism the notion was the child is born as a blank slate, and Chomsky said that it would be absolutely impossible to acquire something as complex as human language if you are really a blank slate."

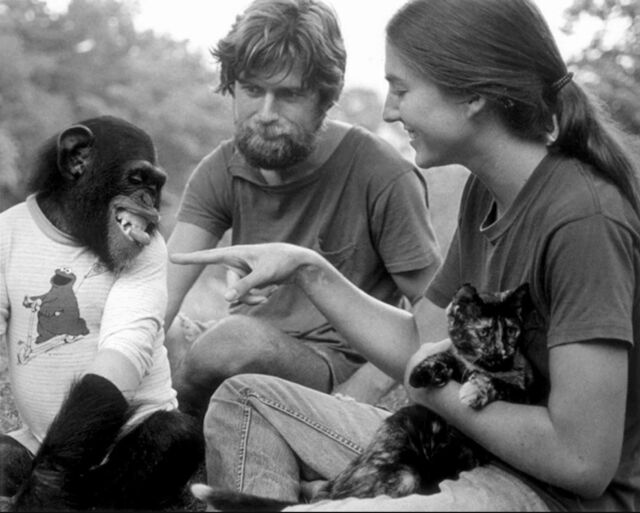

This was starting to sound a little familiar from previous Wikipedia trips. "There was, like, a monkey experiment built in here at some point, isn't there?" I asked.

"Yeah, and people have done that," she responded. "They've raised chimps in their homes as though they were their own children, and the chimps do not acquire language—yet, a child will soak it up effortlessly. So, Chomsky has this notion that there is an innate 'universal grammar' that tells a human infant what is and is not a possible human language. You can see where this fits in with the notion of an alien language, because presumably an alien wouldn't have the same kind of universal grammar."

"You would assume—I guess you would assume—I don't know, we can make the rules be whatever we want," I replied. "But you would assume that for an alien to evolve into roughly analogous sentience with a person, there would be something equivalent to that."

I was feeling a little over my head, but I plowed on. "Would you assume that?"

"I would assume things like symbolism—the symbolic nature of language," Dr. Birner replied. "There were a lot of people who assumed that that was one of the great cognitive leaps that made human language possible—the notion that we can represent one thing as something else, and that's what language is." We represent things in the world with words, and once you know that words represent concrete things, it's a short jump to realizing that words can represent abstract things, too.

Symbolic representation isn't necessarily straightforward, either. "A philosopher named Quine had this notion," she said. "If you're out in the field with somebody, and they point and say 'Gavagai!' and you look and you see a rabbit running through the field, you assume that gavagai in their language means rabbit. But how do you know it doesn't mean 'brown,' or 'tail,' or 'leg,' or 'fur'—"

"Or, 'Look at that!'" I said.

"Yeah, all of this other stuff is present, but we have this whole object notion," she said. "We have a notion of what constitutes a distinct object, and we assume that the word corresponds to that whole object as a default. Would the alien have that notion?"

"So," she continued, "I think you're asking exactly the right question when you're asking not just how could we ask about an abstract notion. There's one level, which is, 'How can I possibly ask an alien, what's your word for friendship?' But do they even have a concept of friendship, and how could you ask about that?"

“A human and an alien are stranded on a desert island…”

I presented Dr. Birner with a hypothetical scenario. If two people were shipwrecked on an island, there's a high likelihood that they'd figure out how to cooperate even if they didn't speak the same language. They both come into that situation with some innate knowns about their shared plight—they both need water, for example. Neither wants to die of thirst. Maybe one of them is a bad person and doesn't want to share any water, but they each innately comprehend both the fact that they need it and also the reason why they need it.

But what if it's not two humans on the island? What if it's a human and an alien (not necessarily Rocky, just some kind of unknown non-terrestrial but sentient being) who get stranded? Where and how do you start communicating?

"I think the movie Arrival did a pretty good job with the notion of, OK, start with, 'This is what I call myself,'" she said. "But I'd have to push it back even one step further, which is to try to establish, 'Do you have labels for things? Do you label things?'"

She continued: "You can't even assume they have things like nouns and verbs. These are things that Chomsky assumes to be part of our cognitive endowment, part of the universal grammar. There are things like nouns and verbs in every language. Why should that be true for an alien language? The naïve answer would be, 'Well, there are actions that you need to label and there are objects that you need to label.' Except that verbs aren't really action words despite what third grade teachers tell kids. A word like stagnate isn't an action word."

I asked her then as an aside—because I was legitimately curious—if nouns and verbs are universal components in all known terrestrial languages.

"Yes," she answered, "but I think there are languages without adjectives. I think there are languages without prepositions. Definitely, languages without determiners. What I tell my classes is a noun isn't a person, place, thing, or idea as you're told. Sincerity is none of those things. The only difference between the word sincere, adjective, and the word sincerity, noun, is where they go in a sentence. The meaning is basically the same thing except that one is the noun form and one is the adjective form. Yet, this whole notion of having sentences with parts of speech that play different roles, that could just be a terrestrial thing that isn't actually necessary to communication."

Perhaps, Dr. Birner continued, a hard syntactical separation between nouns and verbs is simply arbitrary. "We have categories for nouns and verbs that roughly sort of correlate with things and actions, but what about emotions?" she said. "Human beings have emotions. We treat those as things by using nouns for them. But emotions aren't things, so you can imagine a linguistic system that would treat those as verbs. 'I'm happying right now. Earlier today, I was sadding.'"

I brought up something else that would be absent from alien communication, too: "We keep up this constant secondary running communication as we're speaking," I said. "I'm nodding at you, and I'm raising my eyebrows, and we have this back channel." We were doing our talk via Zoom, and as I was talking, Dr. Birner was also nodding along. "You can negate what you're saying by making your face be a certain way. Well, how the hell do you communicate that?"

"Right, Deborah Tannen has this notion of 'message' and 'meta-message,'" she replied. "As we're communicating, part of what we're doing is the message, but a huge amount is the meta-message—which is all that stuff you're talking about. She calls these positive minimal responses, the 'uh-huh,' the nods—the meta-message would include greetings, for example, and it's all just relationship maintenance. Are you and I OK with each other? Am I grumpy? Have you offended me in some way? All this stuff that might or might not apply for aliens—and how would you find out?"

Do Ryland and Rocky work?

We ended up blowing an entire hour on linguistics, and it was easily the coolest and nerdiest conversation I've had in a long time. Nearing the end, though, I asked Dr. Birner for her final take on whether or not the language acquisition exercise portrayed in Project Hail Mary would work.

Her consensus was "probably," but only given a number of extremely lucky—and extremely unlikely—coincidences in psychology and evolution (there's that anthropic principle of science fiction rearing its head!). If we can take it as a given that the alien is "friendly" (and if we can also take it as a given that "friendship" in the alien's society carries along with it the same or a similar set of relationship expectations as it does for humans), and if we can take it as a given that the alien has similar emotional drivers, and if the alien values (or can at least intellectually conceive of) concepts like altruism and cooperation, and if the alien has a compatible sense of morality that places value on the lives of individuals and prioritizes the avoidance of death—if we can take all those things and more as givens, then things might work out.

"I think that given a theoretically infinite amount of time, probably yes," communication would be possible, she said. "As long as there's enough goodwill that you are going to be there together working together."

Of course, there would be limits to understanding, even with all the coincidences. "There's also this thing called the critical period hypothesis," she said, "which says that all of that innateness, all that great stuff that's innate, goes away after roughly puberty. So, that would predict that the alien and I would never become fluent in each other's languages."

So there you go—maybe. But what if there were fewer givens? If we imagine that all of the "knowns" that enable communication are like a stack of Jenga blocks, which ones are the critical ones that will destroy the tower if we yank them out?

Dr. Birner thought about it for a moment, then replied with a short list of things without which understanding likely cannot happen. The first of those things, she explained, is a theory of mind. Both parties need to have some reason to believe the other party has a somewhat similar cognition—that there is some basis for even bothering to communicate.

After that, symbolism is next on the list—both parties need to know that they can communicate in representative terms. This isn't necessarily literary symbolism like in high school English class. This is the notion, as discussed, that words are representative of objects and concepts. The idea that when I show you a clock, for example, I'm showing you a device that measures time rather than just a thing with numbers on it—or the idea that my spacecraft's instrumentation represents conditions inside and outside the spacecraft, rather than just being a bunch of pretty lights and dials.

Then, both parties need some incarnation of the cooperative principle Dr. Birner mentioned earlier—because otherwise, there's no biological incentive to cooperate in the first place.

"But then," she said, "I think a lot of what Chomsky considers our innate human endowment isn't necessary for this scenario—things like syntax." She sounded pensive as she went on: "I think you could have a really, really well-developed communicative system without syntax. You can fight over whether that would count as language—well, at some point, it's just a labeling problem. You need symbolism. You need the notion of communication. You need theory of mind, and you need cooperation. I think those are the real fundamentals off-hand. Everything else, I think, is negotiable."

Can we ever know another's mind?

As much as I love Rocky and Grace's repartee—and it does work, very well—it seems that the most likely conclusion is that the two of them being able to communicate with each other in real life as well as they do in Project Hail Mary is more of a dramatic device than a science-based outcome. Rocky, for all his fun, alien bro-ness, is more or less a human mind in an alien body. He comes pre-equipped with cognition that maps one-to-one against dramatically vital human-specific concepts of metaphor, symbolism, syntax, grammar, cooperation, and altruism. Grace and Rocky acquire each other's language in the same way as they acquire each other's numerical systems, and they exhibit no difficulty (or at least no on-screen difficulty) with digesting and integrating a whole range of abstract concepts.

The contrast with the approach taken by other authors like Cherryh is significant—PHM is a very different work from Cherryh's Foreigner series. This stems more than anything else from each author's storytelling goals. Weir writes with almost a Clarke-ian focus on the setting and the science, with the characters existing primarily as vehicles to enable more fancy problem-solving to happen. Cherryh writes stories about the squishy things that happen when different people mesh together—her stories are set in space, but they are primarily about the internal landscapes of the characters.

Neither approach is necessarily better than the other, but in comparing PHM's take on alien language acquisition with Cherryh's, it feels like Cherryh's is more faithful to what reality might be like. With PHM, the science of language is a means to an end, rather than the end itself. Communication is a box to be checked, and once checked, it's "done." Grace and Rocky continue to learn new words, but their understanding of each other's minds is a binary event that flips from 0 to 1, rather than moving on an ever-expanding continuum.

As we closed, Dr. Birner and I kept circling a last point. What if PHM's first contact scenario happened with an alien that demonstrates very human-like cognition? Would a human and alien pair like Grace and Rocky really be able to work things out?

"Both cultures have communication and communicative intent and theory of mind, OK," she posited. "Now, what? It would take a long time—and again, I think you could get the concrete stuff really simply, but the abstract stuff would be extremely hard, especially because we can't assume that we share any of those abstractions. The real trick is, how do you get to understand whether you even share the abstractions in order to talk about them?"

"Right," I said, newly fortified with a free hour-long class worth of new linguistics knowledge. "We can always, being people—we can always go a little bit further back and then try to catch it back up. There are always assumptions. Eventually, we will hit basic assumptions." But there are no basic assumptions with an extraterrestrial sapient.

"Because their mind is over there, and my mind is over here," she concluded. "How can I check whether we've reached that kind of understanding?"

Neither of us had an answer for that one. We'll have to wait until actual aliens show up—and hope that when they do, they're less like Cherryh's atevi and more like Weir's Eridians. After all, atevi don't do jazz hands.

https://ift.tt/3fVq648

Technology

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Andy Weir's Project Hail Mary and the soft, squishy science of language - Ars Technica"

Posting Komentar